The driver steered his car down a backcountry road that split canopies of great oaks, whose moss dripped from its long branches like Louisiana tinsel. The hardly-traveled road is a place where hawks soar over towering tree tops and deer and wild boar roam unencumbered by hunters’ rifles. On this early morning in August, it is as quiet as the moon.

From seemingly nowhere, a tall wire fence appears, completely out of place in the pastoral setting. The fence reminded the driver to look through the rearview mirror and tell me, “By the way, you cannot write about this location,” he said. “No one can know.”

We were approaching one of the only homes in the United States of America for teenagers who have escaped human trafficking: Metanoia stands virtually alone as a haven for the millions of humanly trafficked.

As I stepped toward Metanoia’s front door, I was told that some of the teens inside had daily been sexually abused by as many as fifteen different men. In essence, these girls awakened each morning to seemingly being pulled from ring to ring in hell.

I remembered a teenage boy in Guadalajara, Mexico telling me one day “he lived in hell” before being rescued by the Sisters of Mary. As I was led into a room at Metanoia, I thought of the thousands of teenage boys and girls who had been mothered back to health by the Sisters of Mary, who climb the world’s most dangerous mountains and walk into the darkest villages to save the most bullied children in the world. To date, more than 170,000 children have been taken in by the Sisters.

Like the 19,000 students at the Boystown and Girlstown communities, the teenage girls at Metanoia Manor in Louisiana have been given hope for a better future. Nearly one hundred percent of juveniles who escape trafficking have nowhere to run to, or to lay their head. Metanoia has only 16 beds for the three million teenagers being trafficked in America today – it is the kind of math causes choruses of guardian angels for the trafficked to weep.

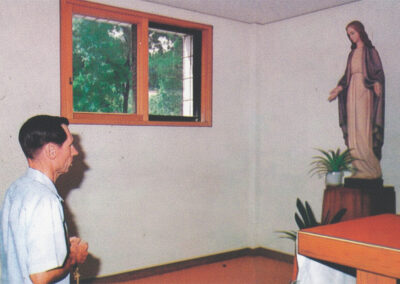

Eleven formerly trafficked teenagers are receiving care on this day from Fr. Jeffrey Bayhi and the five Hospitaler Sisters of Mercy. Similar to World Villages for Children founder Venerable Aloysius Schwartz, Fr. Bayhi fought stiff resistance – to open Metanoia in 2017. The recently-retired 69-year-old diocesan priest will spend the remainder of his life doing whatever he is able to save and care for the trafficked.

“How many more children need to suffer, endure years of sex slavery, and die before churches, legislatures, federal and state governments, and the public decide to answer the question: “Lord, who is my neighbor?” Fr Bayhi said, with his hands raised, palms facing upward. “My dear God. Millions of Americans are buying and selling God’s children. All of us should be outraged. All of us should be thinking, ’What am I supposed to do to relieve the pain and suffering of these tortured children? What is my part in this?’

“In 2001, when I began to learn about human trafficking, the first girl I was introduced to was a 15-year-old who had been raped three thousand times,” he said. “These children have no voice, no one to speak for them. And I have a big mouth, and I will use it whenever I can to fight and speak for these girls.”

Without public support, Fr. Bayhi must raise more than $850,000 from private sources to keep Metanoia open each year. The five sisters live at Metanoia, where they work around the clock to care for, arguably, some of the most soul-scarred teenagers in the world.

Like the 382 Sisters of Mary, these five sisters strive daily to raise the many broken spirits they’ve brought into their place of rescue. Both communities – Metanoia and the Sisters of Mary’s Boystowns and Girlstowns – have become accustomed to penetrating into the horror of children’s memories. Oftentimes, after listening to a teen tell a story of trafficking devastation, a sister will quietly enter an empty room, lock the door behind them, and cry.

Similarly, I watched Sr. Martha, who oversees the Girlstown community on Chalco, shed copious tears one afternoon when listening to seven girls share harrowing stories from their pasts earlier this year. She looked at me and whispered, “Sometimes, I need to be reminded of how bad it was.” she said. “They have overcome so much, and I need to hear how they did it.”

Some of the formerly trafficked teenage girls in Louisiana sleep in bathtubs, closets, or beneath beds. A few carry stuffed animals to kitchen tables. Some use pacifiers and eat beneath the kitchen table. Each one suffers from paralyzing nightmares. A few have been saved by a sister while attempting suicide.

Stunningly, the sexual slavery experienced by these children – both in America and in the Sisters of Mary’s communities – is often forced upon them by their own parents or guardians, who’ve offered their children as sex objects as a means of survival or feeding drug or alcohol addictions.

“I know of parents who’ve taken their children out of school and into the school parking lot,” Fr. Bayhi said, “where a man was waiting for them. After the act, the parent will bring them back to class. The evil is unspeakable, but it is very real.”

There are great moments of hope, though.

In the summer blockbuster, The Sound of Freedom, which chronicled the underworld of human trafficking, a harrowing scene revealed traffickers taking photographs of soon-to-be-kidnapped adolescents in various stages of subtle undress or wearing copious amounts of makeup. None the wiser, the children are told by a trafficker that they are being photographed for an innocent modeling spread.

A quite different scene unfolded last month in Chalco, Mexico, where 783 incoming first-year students – mostly 12-year-old girls – were asked to stand in front of a camera with a small placard in their hand. But in a stunningly beautiful paradox and inverse to the dark movie scene, the girls proudly held up their names in front of a camera so the Sisters could begin to identify each student by name. Their names are known by God, the Sisters of Mary told each one of the students, and for the next five years, they would love them as unique and individual souls. “You are God’s precious ones,” each child is told by the Sisters of Mary.

You are safe here.