CHALCO, Mexico – Last week, I was deep into the Mexican interior on a long and radio-less car ride from Guadalajara to Chalco. My traveling companions were tired and quiet as we passed brush fires high up on mountains, lonesome haciendas and sombreroed cowboys minding slender cattle. Within that quiet place, my mind traveled to what I’d absorbed the previous two weeks.

I considered the Sisters of Mary and the many thousands of young men and women I’d encountered in Catholic Mexican Boystowns and Girlstowns. I glimpsed things no one sees. I’d witnessed what seemed to be miracles.

Kevin with the students of Girlstown Chalco.

After an hour or so, though, of some of the warmer remembrances, I found myself considering the tension between who they are and who I am not. As rusted rectangular road signs pointed to unpronounceable villages, I looked inward. These once-tormented children knew resurrected joy, and conversely, the Sisters knew the life that came from dying – and I was just a Catholic man doing okay in the world.

My thoughts began to settle on the Sisters and their crucified path in life to heaven. No corner of their hearts were left for themselves, I knew; they’d surrendered their lives to stand at the iron gate of children’s wounded souls. Each Sister agrees to the transfer: every child enters the community shouldering a blue-whale-sized cross – the sisters throw out their arms to bear its weight, until like Simon, the cross becomes entirely theirs. I began to pray: Dear Lord, have mercy on me. These little ones are the answer to the world’s pain; they were dead and now alive. These humble Sisters are the answer: they were alive and now they die. Don’t let me float insufficiently in the middle.

The Sisters of Mary during their Mother’s Day celebration.

How does one end up in sun-splashed Mexican heartland, praying in an eastbound-traveling car, during a pandemic?

In April, I had the thought to travel to Chalco to be with the Sisters of Mary. The idea was simple. With Americans video-conferencing in pajama-bottoms, I wanted to be in the company of those whom I’d recently come to discover as blue-collar martyrs. Their congregation is scattered throughout South and Central America and the Far East like spilled chalices of the Lord’s Blood. The Sisters of Mary are considered by many to be the hardest-working congregation in the world.

I wrote a book in 2019, The Priests We Need to Save the Church, that saw some success, and afterwards I discovered this priest – Venerable Aloysius Schwartz. I believe him to be he is as impactful as any priest who’s ever lived.

A group of students gathered around a statue of Fr. Al in the middle of campus.

Before Fr. Al’s untimely death in 1992, he handed the baton to his spiritual daughters, the Sisters of Mary. As a writer eager to hold his life up for the world to see, I wanted to see his heirlooms at work. I somehow convinced Sr. Margie Cheong, the Korean-born Sister and head of the Latin American communities of Mexico, Guatemala, Brazil and Honduras, to grant me access into their communities.

After landing safely in Mexico City in early May, I became subject to a new rite of passage at a nearby clinic – a pair of three-inch wooden Q-tips were pushed into the upper reaches of my nasal passages. “All for Padre Al,” I whined to Sherlyn, my translator, through watery eyes.

Once cleared of the virus, I entered past the iron gates and high stone walls of Chalco and became flabbergasted. This was the first thing I saw: a fully-habited sister jogging with more than 300 teenage girls in tow. Each looked to be smiling. Because American sensibilities were not yet shed, Rocky and those hundreds of city kids who tried to keep up with him as he leapt Philadelphia park benches came to mind. To my left, a fully-habited sister was full-tilt on a soccer field filled with girls.

A Sister of Mary going for a run with a group of girls.

As the day unfolded, I became lifted into a different dimension, one unseen in America. For starters, 3,300 teenage girls were without cell phones. They prayed the rosary at 7 p.m. in a harmonious chorus that reverberated like orchestral hives of bees. As the setting blood-red sun reflected its light off twin snow-capped volcanoes in the distance, I watched the girls press into the gymnasium for catechism. An hour later, they poured out like happy saints, smiling, waving and welcoming the stranger in their midst. The volcanoes seemed to stand prouder then, like glowing Fathers absorbing their daughters in the fading light. It would have been okay if time had stopped right then.

A few nights later on the Feast Day of Our Lady of Fatima, the 3,000-strong caravan knelt on hardwood before the exposed Blessed Sacrament for the better part of an hour. I didn’t observe any fidgeting; it was as if they were kneeling on cashmere-lined pillows; None I saw rubbed their knees exiting the gymnasium. I was reminded of the Major League Baseball player, who after getting hit in the forearm with a mid-90s fastball, doesn’t give the pitcher the satisfaction of knowing it hurt.

Students and Sisters gathered to pray on the feast of Our Lady of Fatima.

Girlstown in Chalco and Boystown in Guadalajara are saving grounds; sanctified fields of good will and resurrection. Children throb with a startling type of joy, heightened by the knowledge that they were lifted from harsh lives of poverty. It took a while to figure out why the teenagers addressed each of the Sisters as Madre. “We are spiritual mothers to them first,” a sister told me. “They have been through too much.”

These Sisters are bright Hallelujahs set into souls. Their medicine is light, joy and service because they know many of the children have worked fields, barefoot, at the age of 8 or 9 and returned home to find no food on the table. Zayra, one of them, revealed to me that she was chased an hour up Loma Larga Mountain by a human trafficker. Her grandfather, on that mountain where she lived, was drunk most nights. “I would kneel in front of the statue of Mary and pray the fights and drinking would stop,” she said. Antonina, an orphan, told me her father was shot dead in the street. Her mom, she believes, burned to death.

But oh, how Zayra and Antonina smile now – not a painted-on Catholic Branch Davidian-type. But a smile that speaks of how the Mothers have placed Christ back into His rightful place in their scraped-up souls. For the five years the Sisters will have them, they educate, nourish, catechize, play, jog and pray with them; they do not stop. The eloquence of their maternal love – given ever so slowly, so tenderly – pulls away layer after layer of wounds and horrors too graphic for this writing.

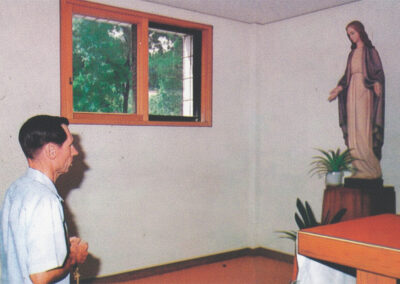

Kevin with Sister Marinei.

Each of the Sisters greeted me as Mothers do their sons arriving home from war – but I knew I was just in the way. Their duty was the children. “Time here is like Magdalene’s perfume; it is precious for us,” Sr. Margie said. “We give all we are to them.” The Sisters know the secret: persevering love stirs hearts into healing.

I had befriended cheery-eyed Brazilian-born Sr. Marinei (pronounced Mar-en-ae), who prepared my meal each evening. One night I asked about the toughness of her work.

“To live poverty means that I must accept a certain death, she said. “I know I need to die several times a day. I need to leave behind everything that I am. But that is the Gospel – I leave everything – mother, father, all that I have.

“This is what Jesus asks. It is difficult, but these difficulties are great gifts. Because they allow me to offer myself fully to Him and these girls.”

It is Jesus Christ, spread out everywhere here. And it is within this holy paradox of living and dying – this letting go of crosses (the children) and comfort (the Sisters) – that seems the most reasonable thing in the world.