So, how did this mission even start?

Who or what was the catalyst? Venerable Aloysius Schwartz kept the secrets of his interior life very close – and he was too busy to wax nostalgic about his early motivations, inspirations and movements of the Spirit.

“How, then, does a mission vocation begin?,” Fr. Al asked, rhetorically, in the book The Starved and the Silent. “Gradually or suddenly? Dramatically or matter-of-factly? In a flash of light, or as a result of years of searching and stumbling?”

Fr. Al as a young seminarian.

What was the spark that pushed him to step into the lives of hundreds of thousands and lift them to better places? The answer lay hidden in the summer of 1943, on the front porch of a convent in an impoverished section of Washington D.C. It was there that Fr. Al, as a 12-year-old boy, sat at the foot of his aunt, Frances Schwartz – Sister Mary Melfrieda.

On Sundays, Fr. Al’s father, Louis, used to take his family on day trips, where he would load the Schwartz’s into his second-hand Nash Motors sedan, with high-mileage and white-washed tires, and head off to nearby Maryland beaches and rivers and to tourist spots throughout Washington and Virginia. It was at one of these destinations where providence struck.

Louis headed south one Sunday afternoon down Benning Rd. and onto Kenilworth Avenue and into the community of Anacostia, where his older sister sat on the porch of her convent at one of the highest points in town awaiting them. “Dad’s tires would start spinning out climbing that hill. With all of us in there, we would always struggle to even make it up that hill,” Al’s older brother Lou remembered. Sr. Melfrieda was a missionary with the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, where she taught the black students of Our Lady of Perpetual Help mission on Morris Rd. Her order was founded in 1804 to serve the powerless, voiceless, and societally disregarded in France.

Sr. Melfrieda’s tucked-away convent, so far away from the noise of the city, seemed to sit on a Siberian mountainside. It offered the Schwartz children striking panoramas of the tidal basin, Potomac River, Lincoln Memorial, Washington Monument and other D.C. landmarks, but also of a wide swath of a neighborhood that seemed a landscape of neglect. While his siblings gawked at the far-off views and picked from the assortment of treats Sr. Melfrieda laid out for them on the sweeping front porch, Al sat at the foot of a nun who flipped his entire world, opening his eyes to regarding poverty as the privileged path to God. This first encounter marked the piecemeal turning point of his life, where he discovered that his own life – on society’s lower rungs of the ladder – was directly in line with the life of Christ, who was born in an animal stall and whose parents offered as a sacrifice two turtle doves because of their lowly state.

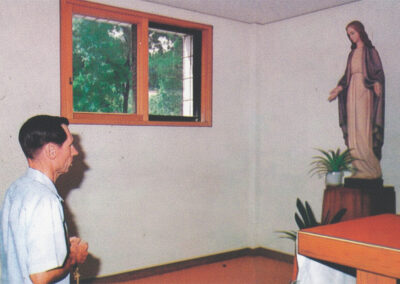

Fr. Al after his arrival in Korea.

Sr. Melfrieda told Al that lived poverty meant living close to Christ and stepping into the same darkness of poverty in which he chose to reside. The thought compelled him. His aunt spoke to him of immense realities he had never before considered: she introduced the Savior as marginalized and poor, just like the black children living in the small homes in the narrow lanes of the neighborhood that surrounded her.

“I think it was then, in [Sr. Melfrieda’s] presence, that Al began to slowly understand God’s plan for him,” Lou said. “He wanted to be among the poor, and he wanted to serve them as Christ did.”

Al saw that Sr. Melfrieda had embraced the poor Anacostia neighborhood and made her small convent and schoolhouse a humble Kingdom for the poor. Her glow and gentle manner told him she was at home among the poor. It was from that porch that Al began to see that the fruit of those things truly beautiful arose from obscurity and sacrifice. God’s reparative work for a fallen world, she encouraged Al, had to come through the hands of those willing to rub life back into the societally leaprous. It was here, at this high elevation in Washington D.C., where his missionary heart began to stir; he saw that the greatest measure of love was sacrifice.

Fr. Al serving the poor children of Korea.

He begged his father for return trips, where his aunt continued to tug at his heart with little tales of her care for the children. As his siblings frolicked in the spacious acreage that spread out around the convent, Al and his aunt were establishing a spiritual bond. He saw the cross of her long days with the poor as the sanctifying work of God. She had renounced the world to serve those renounced by society. Her convent at the highest point in D.C. seemed to Al a mountain hermitage centered in the heart of God’s most treasured souls: the poor, disregarded and humiliated.

By autumn, Sr. Melfrieda was gone, but the mysterious undercurrents of God’s movements had been set into motion. His aunt was needed as Superior at all-black St. Augustine School in Buffalo, New York. She was rarely seen again. Included in her obituary from September of 1959 are these words: “Her heart went out to her colored charges, and she gave them the full measure of her devoted love. Sister Mary Melfrieda was a real apostle. She saw Christ in the dusky face of every colored child she taught, and tried to make him realize his dignity as a child of God and a member of the Mystical Body. Every lesson she taught was impregnated with this one idea: Her little pupils did not have much in the way of worldly possessions, but she wanted to make sure that they would be spiritually rich.”

Fr. Al’s obit 33 years later would read remarkably the same.